Margaret Carr Kearney.

Her Confirmation, at Holy Rosary Church on Kelly Street, brought her not the promised nylons, but "the lend" of friend Joan Stanton's leg paint. Joan was a schoolmate whose father was an Officer in the U. S. Army. Her house at Bennett and Murtland contains ivory curios and pillows emblazoned with "Remember Pearl Harbor" in red, white and blue letters. It was during religion class that both Margaret and Joan were called to the office of the principal to hear the news that Margaret should accompany her friend home right away. She remembers the dread on her friend's face upon seeing the parked army vehicle: "My Dad is dead!" An assumption that was tragically true.

However, Margaret Carr's most vivid memory of those early forties was filled with a different type of dread. She had heard her Irish-born Mother and Dad whispering, and noted that her father, usually outgoing and cheerful became unusually quiet and tense when a knock came at the door. Her aunts, Sarah and Katie Henry, visited their sister Bridget more often. The word "deportation" was whispered and the look on her mother's face was one that Margie had never seen before. Her mother's voice was shaking as she said

"But we have four children, I am naturalized, he's a hard worker---the A & P would stand up for him. He had to come in the 'back door,' times are still hard back home. We've never been in any trouble, we can't go back to Ireland. He said he would gladly fight for this great country but now we are afraid to 'say something'...maybe Jimmy will be fired, or deported back to Donegal by himself. Then where would we be?...Ireland is neutral. The English are now this country's allies.... Maybe they'll hold that against us."

The conversation always stopped when someone especially the children, would enter the small living room at 7113 Frankstown Ave. But the dreaded day did arrive. And with it, the story of how James Carr and several Pittsburgh Irish had left their completed Canadian agricultural jobs, paid one hundred dollars (each) to be loaded into a trunk of a car headed southward to Buffalo, New York. Jim had been fourteen when practical necessity dictated that he leave the northernmost area of Ireland. He wanted to find a "better life," first in Scotland, then as a "hired hand," cutting wheat in Saskatchewan, Canada. Margaret had already heard the story (told without any trace of self pity) of the "compassionate" rancher who took pity on the six Irish and Scottish "hands." Realizing that, by morning, his employees would be found in the unheated stable frozen to death, he allowed them to take the blankets from the horses. All the lads agreed that even the frigid weather of their homelands had not prepared them for the sub zero temperatures of the Canadian province. The songs of their native lands contained lines about how the "Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave...Amerikay" would welcome immigrants. But not just at that particular time. The quota, in the late twenties, just about shut the door to anyone seeking work in depression America. Margaret recalls hearing how lovely Fanad, Donegal and Sligo mountains were and can still hear her parents stock reply: "You can't eat the scenery."

The parish priest, Father Kerr, was consulted, the bosses at the A & P were willing to state that Jimmy Carr was an extraordinarily hard worker and the warehouse would be hard put to replace him. Testaments of his good character and standing in the community were provided. Neighbors Bernice Griffin, local pub owner, Jim Donovan, and the entire Carr and Henry Families went to the court house and federal building for the "legal proceedings." In the end, James Carr (after successfully completing the "citizenship test," which included discovering Patrick Henry to be a great American patriot...not just the name of his Sligo brother-in-law) was made a very relieved citizen of the United States of America. His age, status as a father of four, and his being a valuable employee of the food industry exempted him from the draft. He and his family were everlastingly grateful to what they would call "the greatest country in the world." Churchill was now viewed not as the enemy of a totally free Ireland but as "Winnie" who was helping in orchestrating the fight against the world's Evil. Margaret and her sisters often attended the Belmar show and saw the newsreels showing the British Prime Minister flashing his "V for victory" sign. As she matured throughout those later war years, her memories included a feeling of security, even though reminders of "the war" were part of every day life. The soldiers were brave heroes. Her family was safe (even during blackouts) and the "duration" had become normalcy.

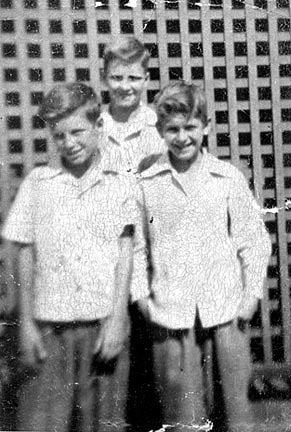

John "Butch" Fitzwilliams.

John "Butch" Fitzwilliams viewed those years through

slightly younger but more excited eyes. He states "they were a great time

to grow up. The nation had a purpose, and that purpose filtered down to

each and every American, regardless of age." His mother was said to ask,

upon hearing Pearl Harbor had been attacked "Who is she??" His

father, John Fitzwilliams, worked in Jones and

Laughlin steel mill. His uncle Henry "Hank" Wank was in the Navy and had

a ship sink under him. If family lore is to be believed, he had

just finished reading a letter from the Naval Department of Discharge

stating he was now

"discharged because of age, thank you for your service and good luck in

civilian life." The nine-year-old Butch was a member of the Homewood "Jr.

Commandos" and his "Commander" relative did not question where the boys

had obtained so much scrap metal. It turns out that they had "recovered"

(stolen) it from an empty house. A trip to the "junkies" (salvage yard)

with laden down wagon and sleds (in winter) was exciting. Although

the young patriots remembered to mind that the junkman didn't "short" them,

they took preventative measure by placing flat stones in between the newspapers

(Homewood Brushton News, The

Needle, The Sun-Telegraph. The "junkies,"

adjacent to Silver Lake, was full of young children

doing their part in the "War Effort." Kids were still kids, however.

He remembers his gang waiting at the streetcar/bus stops to watch riders toss in the sand in the gutter their long, flavorless, "Wings" cigarettes. "Luckies and Chesterfields" were hard to come by. The gang would retrieve the long butts of the cleanest looking people, take the tobacco out and then roll their own "new cigs" using the "Bugler" paper of cohort Georgie Kirk's father. He recollects his mother working outside the home and the freedom that provided for him and his older (by two years) brother Jimmy. Movie houses were many kids' second homes as business at the Belmar, Hiland and Brushton theaters boomed. Often the gang would walk along the railroad tracks into East Liberty to see shows at the Enright (amateur hours) or at the nearer Liberty with its several-stories-high neon display of the American Flag. The "chapters/serials" showed everyone fighting the "Nazis and the Japs"...Tarzan included. The cartoons showed a goose-stepping Fuhrer and a yellow Hirohito. War bonds were sold everywhere...at Holy Rosary School, at the theaters, the Post Office, and at every workplace. He remembers going to see Lucille Ball and Kay Kyser, the bandleader at the Stanley Theater. He remembers another singer coming on-stage, hair in "do-up" (a fractured memory of "Up-do"; the hair-do necessitated by factory work) and her singing: "Any Bonds today? The Bonds of Freedom is what we are needing.... Any Bonds today...?" He also recalls a parade in downtown featuring the English actress (Mrs. Miniver), Greer Garson, and the singing Andrews Sisters.

Memory can also be a tricky thing, Butch states. He recalls attending (he thinks it was at Forbes Field or Pitt Stadium) an event called "War Games." Who sponsored them he doesn't know, but recalls (and his pal "Irish," from Morningside, concurs) that the teams represented "Us" and "The Enemy." Dressed in red for one side and green for the other, they simulated hand to hand combat, shooting weapons, and actually had a tank come on the field during the big finale which included planes, (rare in those days) as they flew over the Oakland sports field. At the end everyone stood and sang "God Bless America."

The Armed Services represented the ultimate in hero worship. Anyone who was "4-F" was either scorned or pitied. A fist fight of two Marines outside the White Hawk bar brought out an audience of all ages. Butch remembers the two (on-leave) Marines, "Dodo" Diorio and Jack Lee taking off their leather belts and wrapping them around their fists. He says no one even thought of calling the police or the Military. He recalls returning "boys" who had changed. People said they were "nervous from the service". The term "section eight" (unfit for military service because of mental deficiency) became part of the common vernacular. All Americans were expected to be brave. He remembers his Uncle Bob Scherer, a policeman at No. 13 in Oakland getting so mad when he heard that Hitler had termed America "a mongrel nation." His parents were from Germany but had come here, to find a better life. The idea of "Aryan" purity was ridiculous. Butch remembers the ethnicity of Pittsburgh. In Homewood-Brushton the Irish lived all over but lots on Monticello Street. Irish "belonged" to Holy Rosary parish with Father Cougley. The Italians from Tioga street (with the exception of pal Norman Agazolli) went to Mother of Good Counsel or Help of Christians in East Liberty. Cousins in South Side went to St. John's, their Polish friends to St. Adalbert's, Slovak acquaintances lived "down the run" which was the four-mile-run, a lower Greenfield neighborhood. St. Joachim's was their parish. The only "colored" (as African-Americans were then termed) Butch knew well was Holy Rosary School classmate, Johnny Russell, who lived "down the next alley" (Formosa Way) behind the church.

Juvenile scatological put-downs included anything dirty being termed "Hitler." Anyone with "slanty-eyes" was subject to criticism. The "Tea Garden" restaurant, on Kelly Street, was decorated with American flags. Y. Y. Yee, the Chinese laundry man, who knew "everyone's business," was vocal in disassociating himself from other Orientals. Pictures of his relatives in uniform were prominently displayed in his shop.

Both Margaret and Butch remember the day the war ended in Europe--VE Day. Everyone took to the streets in a massive, spontaneous celebration. Hitler had been defeated and those boys that were in the European theatre (strange term, both noted, for such a bloody venue) would be returning. Neither remember any thoughts about a pending end to the war in the Pacific. On Homewood Avenue (and all traffic routes) people were jumping on and off of buses and streetcars. The men and women from the car barns (three blocks of storage and maintenance facilities for Pittsburgh Railways streetcars) came streaming out of their locations. The bars and taverns were filled to overflowing with folks that normally would not have visited these premises. Shop owners wisely gave their employees time off and closed. Many, including the Fitzwilliams' went downtown (dawhtawn, in Pittsburghese), Butch jokes. Margaret remembers her family going to Holy Rosary Church to light candles of gratitude. Memories forged in "the duration" would last a lifetime.

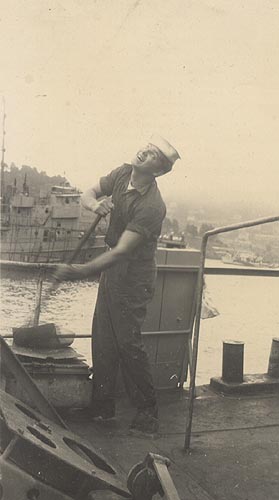

Clarence Christ.

Somewhat different was the experience of Clarence

Christ, a seventeen-year-old Bloomfield boy who "thought it was his duty" to join

the Navy and does not regret one moment of the following experience, that few

now live to share. Clarence was member of the "H-Hour" (initial landing

force) of the D-Day invasion at the Beaches of Normandy on June 6th,

1944. He was one of six children born to parents of German descent, who

spoke German in the house when they "didn't want us kids to

understand." The family had lived in Garfield but

the Depression brought the loss of that house and so they moved to

St. Joseph's Parish in Bloomfield.

He left Connolly Vocational High School to obtain a job with P. Duff and Sons on Duquesne Way in Pittsburgh. They were manufacturing a new product: cake mix. He was a six footer who was happy to hear that the office girls were encouraged to write to the servicemen and that the company would even save your job and mail incremental bonuses to the employees in the Armed Services.

The Navy beckoned and Clarence joined. He identifies himself as "completely virginal...uninitiated in every way" as he got off the train at Great Lakes. He was astonished to find that one could drink all the "three point" beer one wanted on base, but because his ID card read MINOR, he could not get a drink in Chicago. He was assigned to go to Virginia to "small boats training." In the winter of 1943 he found himself in Scotland, where "the snowdrifts was sometimes ten feet tall." His company was awaiting the return (from Africa) of landing crafts, LCATs on lend lease to Great Britain. He was trained as a coxswain (driver) and the scuttlebutt was that they would be participating in the invasion of German-held France. He traveled south to England's Portsmouth and Dorchester ports. His impression was that England was so very crowded. He later learned that he was but one of the one million, five hundred thousand American servicemen there who were, as the Brits liked to remind them, "over-sexed, overpaid, and over here."

By now the eighteen-year-old was "initiated." He remembers being in a pub and seeing an English girl trying to decide who, out of the many Yanks, was going to be granted the pleasure of "taking her home." Christ, (pronounced Chris) did not take part in this contest of "who the girl found to be the best kisser." She playfully asked him what was wrong. He then reached over and gave her a brotherly kiss on the forehead. He laughs at the memory of his buddies' faces as he left the pub with the girl.

Such lightheartedness was short-lived as spring brought definite battle plans helped along by reconnaissance planes flying across the channel dropping aluminum strips to fool the enemy radar. They were also aided by the "Free French" resistance organization. Christ looks back at the invasion and is quick to modestly point out that he was only a small part of it. On June the fourth, the weather changed and the plans had to be delayed by 48 hours. He knew that some decoy ships had been sent out and news "leaked" to fool the Germans, whose bunkers were said to be impenetrable. He studied the maps and instructions given to him and became one of the 865 USA naval vessels flotilla. He then said his prayers and steered his eleven man LCAT 2008 for sixteen hours across the English Channel to Normandy Beach. His ship contained rockets, a sharpshooter sailor (for mines), a small mine sweeper device and most importantly three specially equipped amphibious tanks. What he saw ahead was a narrow beach shadowed by the tall heavily defended cliffs which the "boys" (transported by other landing crafts) were to capture. What was it like? Clarence Christ, thankfully, is still here to tell us...It was HELL.

Saving Private Ryan, a recent movie that Christ's sons persuaded him to attend was an accurate description of the carnage witnessed. With one exception, Christ points out. The film lasts three hours...the experience itself lasted three days. Sixty-five hundred Allied Forces were killed the first day. What he personally remembers is..."just doing what I was told. But oh yeah, they (the Axis) had to be stopped." Night and day, the relentless shelling and attacks and counterattacks went on. As he went back to the supply ship, they were told, without much tact, that they were not expected to have returned. Hence the short supplies. In fact, of the eighteen LCATs, his was the only one to return intact. His feelings then, he recalled, changed from those of a boy just anxious to spend his "invasion money allowance bonus" to a man who knew he had taken part in a bloody but successful military victory. So sure of the enormous human life costs, were the "higher ups," they had already sent his Mother an MIA [missing in action] telegram.

The 82nd and 101st Airborne would meet up with the tanks Christ and his counterparts had deployed further inland. Navy battleships bombarded the shore constantly. The Special Forces Rangers attacked the embedded "impenetrable" bunkers at Point du Hoc. Only ninety five of the two hundred and twenty five Rangers would return. The second night there, Christ's vessel was shot upon from shore by what they knew had to be our own troops. An order to desist was not successful, the "friendly fire...probably kids checking their weapons"...did not stop until the sailors returned a few rounds over the heads of their beached comrades. Clarence Christ heard the talk of many drowned personnel and is still amazed, given the enormity of the task, that victory was assured in what seemed forever, but was really just three intense days of fighting. His time at Normandy lasted approximately two months, part of that time he spent helping to create an artificial harbor (partially made up of sunken ships) for the bigger vessels to dock. He also remembers transporting strange men with Mongol features that the Germans had placed (prisoners of war, he supposes) as the first line of defense on the beach. One enterprising US sailor visited the now defunct telescope sites of the Germans and pried the diamonds from the precision instruments. Shortly, he had a small bag of diamonds, "booty" for his part in the horrific battle. All knew they were lucky to leave France alive. These months of fighting and enabling others to go inland to fight some more took its toll on all the young men. So with his commanding Officer and his ten crew mates, Clarence steered the LCAT 2008 eastward to England.

Death, however would visit his ship on its return voyage England. The returning voyage was just as turbulent as the way over. Strong winds and waters washing over the deck added to the "stress of survival." A still scared fellow sailor misinterpreted an "all hands on deck" order. Clarence says he will never know what the man was thinking; but, he remembers this young man jumping up and, without donning a life vest, jumping over the side. He was never found. England was the first stop in his return. He spent some time in a "rest camp" and some additional time in London. Now the complete seasoned veteran, he remembers (but won't say from personal experience) the economy of the prostitutes. A "session" was obtained for twelve dollars. But for twenty dollars, the session would include a stay overnight in the girl's apartment.

By the end of 1945, he was stateside in Boston. There, he received a seven-day leave and an assignment to the ACORN division which furnished/maintained Naval facilities. He spent his leave getting across the country with a stop in Pittsburgh to visually assure his parents he was okay. His transport from Pittsburgh was a converted boxcar. In California, he quickly grew tired of furnishing WAVEs with breakfast and volunteered again for sea duty. He got the okay and left for what would be a two year stint in the Philippines. Thus he earned all the medals/ribbons associated with the European and the Pacific theaters, including the Bronze Star. In the Pacific he did not see battle, but supported the efforts of the Pacific fleet. At the end of his military career he was making forty-nine dollars a month, more than twice as much as the twenty-one dollars given to him in boot camp.

But money was not the reason Clarence Christ had served his country. No amount could be enough to make up for what he experienced. These are the author's observation, not his. This modest man, father of seven, married to Kitty Flaherty Christ for 53 years would never agree with that statement. He "just did his duty." And, if the choice were put to him again, he would make the same decisions. He did not, however, choose to join any veterans clubs after discharge. He was characteristically quiet over these many years. Only after much coaxing did his family persuade him to take part in the 50th anniversary of D-Day sponsored by the U. S. State Department and the grateful countries that participated in that day that changed the course of history. His revisit to France brought an unexpected reunion with one of the LCAT 2008 crew members--another stroke of luck in what Clarence Christ considers an ordinary life.

Money, however was very much to the fore, when sometime after returning from Normandy he fell ill with a virus which struck his liver and threatened his life. His HMO requested $250,000 dollars to wait list him for a transplant at Presbyterian hospital. He was unaware that just up the hill was the finest transplant facility for Veterans in the country, perhaps the world. Through a son, who is in the medical field, he was urged to contact the Veterans Hospital. At long last, the U. S. government had an opportunity to help this Pittsburgher who had "left a boy and returned a man," so many years before. He received a liver transplant almost immediately and in true Clarence Christ style, recovered nicely and is now looking forward to the birth of his twelfth grandchild and first great-grandchild.

So ends the "Near And Far" memories of three Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania people: Margaret Carr Kearney, John "Butch" Fitzwilliams, and Clarence Christ. Their narratives have presented diverse recollections and varied witnesses. Their oral histories demonstrate the glorious naivete of that era, and the unquestioned patriotism not demonstrated in today's inherited peace. Each has a unique story. What unites all three, however, is their fervent wishes and earnest prayers that no present or future generation will experience yet another World War.