An Interview with Ruth L. Baxter.

Ruth L. Baxter lives in

Dravosburg,

Pennsylvania, in the same home that she

has lived in for over sixty years. She was born in 1915 and was 26 at the

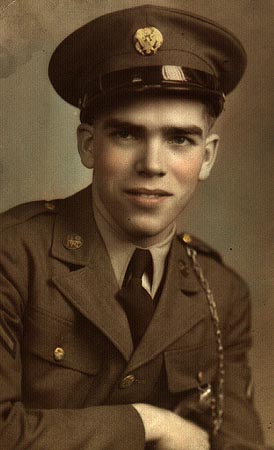

time that Pearl Harbor was bombed. Her husband, Douglas, was drafted and

left to go overseas on December 2, 1943. Ruth recalls this date vividly,

since her son, Douglas, Jr. was about to turn one year old on December 11,

1943. This was the start of a three-year period that Ruth spent on her

own, with her young son. Doug, Sr. served his country, spending all of

his tour of duty in Germany, until January 20, 1946. In his absence,

Doug, Jr., celebrated his 1st, 2nd and 3rd birthdays without his

father.

Ruth resided in a small quiet community and the sight of a police call was an uncommon event. During the time that her husband was involved in the war, Ruth recalls the anxiety that came over her each time that a police car drove up her street and feared the worst. She prayed each time that the police car would not stop at her home, since during the war this was the means by which family members were notified that their loved ones had been killed in action. Those days, months and years were very trying.

Ruth showed me several of the ration books she was issued during World War II. Most were empty, except for one that had coffee stamps remaining. She explained that staples such as sugar, butter, and eggs were rationed in order to help supply our troops over seas and therefore were difficult to obtain in stores. She had another ration book that had previously contained stamps for shoes, not for her, but for her young and growing son. All of the books were issued by the US Office of Price Administration, Local War Price and Rationing Board No. 262-11, which was located in Munhall, Pennsylvania. The following excerpt taken from the "Instructions" section of the books indicates the value and spirit necessary at that time for a nation to pull together to support the war effort:

1. This book is valuable. Do not lose it.

2. Each stamp authorizes you to purchase rationed goods in the quantities and at the times designated by the Office of Price Administration. Without the stamps, you will be unable to purchase those goods.

Rationing is a vital part of your country's war effort… Any attempt to violate the rules is an effort to deny someone his share and will create hardship and discontent. Such action, like treason, helps the enemy. Give your whole support to rationing and thereby conserve our vital goods. Be guided by the rule: 'If you don't need it, DON'T BUY IT.'

The books also contained a warning which indicated that someone who violated the rules for the ration books could be imprisoned for as long as 10 years or fined as much as $10,000. The warning also said that the book could only be used by the person to whom it was issued and could not be transferred to another person.

Ruth recalls sending various items to her husband while he was overseas including letters, baked goods, and cigarettes. She remembers that all mail was censored. The letters that she received from Doug, Sr. were stamped as such, and, on occasion, she received only partial correspondence. Pieces of the letters were literally "cut out" with scissors by the military. The mail was also slow, even at the conclusion of the war. The censoring and the slowness of the mail is evidenced in the following excerpt from a letter written by Doug, Sr. to Ruth and Dougie dated July 5, 1945, which states:

"I can't understand you saying that you had only received two letters from me in the last month. I haven't written every day but I have written you about every other day except when I have been moving and when I went to see Frankie I missed a couple of days but you should have received at least a dozen letters or more. I can't understand why my mail seems to be so late getting to you unless it is the fault of the postal department in the States being unable to decipher my writing."

On a different occasion her husband requested that she send hot chocolate over to him in Germany. Ruth obliged. She asked in her subsequent letters to him if he had in fact received it. He had not. Doug explained to Ruth that his commanding officer also conducted his own "censoring" of the incoming mail and had confiscated it out of the package before it was delivered to him.

Compensation for military service was not much. Doug, Sr. earned $85.00 per month, $35.00 of which he retained for living expenses while in Europe, and $50.00 was sent back to the states to Ruth to care for herself and little Dougie. Therefore, in those days, Ruth had little money, but recalls that she always managed to gather together enough funds to purchase war bonds. She told me about one such occasion, when she scraped together her last $17.50 to purchase a war bond from a volunteer salesperson. While the transaction was taking place, the salesperson told Ruth that the bond effort had been a great success and that there was going to be a banquet that evening in honor of all who had contributed their time to the sale of the bonds. This angered Ruth. She told the salesperson that the money that they were going to use for the banquet would be better off spent for additional war bonds in support of the troops.

As if the man-made war was not bad enough, Ruth also faced a natural disaster that occurred in the late spring or early summer of 1944. A tornado touched down, causing damage to several communities in and around the Dravosburg area. The front and back porches of Ruth's home sustained severe damage caused by the high winds. The Red Cross came to her aid and helped out with the cost in the amount of $96.67 to repair her front and back porches, a broken window and to replace a gutter. Ruth showed me a copy of the well-preserved contract that she had negotiated with the Red Cross for the repairs. Ruth's husband finally returned home in 1946 with a Purple Heart for the injury he sustained during the Battle of the Bulge. It took a little while for 3-year old Dougie to get used to the new stranger (Dad) in the house and to begin talking with him. The three years apart was a lifetime for Dougie and they had never had a chance to bond during his first year of life. But all was right again with the world in 1946 as the family was reunited and World War II was put to rest.

An Interview with Robert Nichol.

Bob recalled how the war was present in all aspects of everyday life. At school, scrap drives were held. He explained how he and his friends helped by collecting metal items from their homes and from around the neighborhood. The items were recycled and used to make products for the war effort. An afternoon at the movies always started off with the latest newsreels that contained film footage of the various events happening in Europe and the Pacific. Bob explained that right after Pearl Harbor and throughout the war, severe prejudicial feelings against Germans and Japanese were common. This kind of animosity was held by most of the folks he knew.

On August 28, 1944, Bob turned 17 years of age and decided to enlist in the military. He and a few of his friends were "gung ho" to help with the war effort, even though they were not 18, the age required to sign up. Bob also added that joining the service was an "easy" way to graduate from high school, since his grades were not that good at the time. While serving his country, he could also receive his diploma. With parental permission in hand, he and three other young men left their high school French class and went to the Post Office in downtown Pittsburgh to register. He recalls that his French teacher, Ms. Susie Simms was very upset to see the young boys go, but she could not talk them out of it.

After signing up, Bob and his friends boarded a train from Pittsburgh to Buffalo, New York, and were off to boot camp. The entire train was so crowded, packed full of military men, that he literally had to sit, as well as sleep, in the aisles. There was absolutely no free space to be had. Because of this, he was kicked more than once and the civilian clothes that he was wearing became very dirty, and, in some spots, stained with blood. When he sent these clothes back to his parents, he was sure to include an explanation of why they contained such stains, so that no one would worry.

Boot camp consisted of nine grueling weeks in Sampson, New York, near Geneva. The make up of the new recruits in his company ranged between 17 and 36 years of age. Bob met some men from Pittsburgh. Two, in particular, were from his home town of Monongahela, Pennsylvania, but there was little time for socializing. As Bob remembers, boot camp consisted of "drill, drill, drill" and "eat, sleep and drill". He, as most, did what he had to do so that the company commander would not reprimand him.

Near the end of the war, in mid-1945, Bob was assigned to the Midway. The Midway was a large air craft carrier, named after the great World War II battle in the Pacific. He remembers that the Midway was approximately three football fields long, with 5,000 crew members, six mess areas for eating (this number did not count the officers' mess halls), barber shops, ice cream shops, and stores that had cigarettes, clothing and stationery for sale.

The Midway had been commissioned early in 1945. Bob was on board as it headed to the North Atlantic for the "Frostbite Expedition", a 28-day mission in Greenland. He remembers how frigid the weather was and the huge amounts of snow that would accumulate on the carrier's decks. He explained that there was so much snow that it had to be "pushed" from the decks by tractors. He recalls his feelings of joy at the conclusion of the mission when they sailed back into warm waters.

On a final note, Bob was at 42nd Street in Times Square in New York City the day after V-E Day. There were massive crowds that filled the streets, celebrating the allied victory. Bob remembers that the Waldorf Astoria, the Stork Club and "21" were open and drinks and food were "on the house". Everything was free to servicemen. Bob described it as "one big party" in which he participated.

Bob returned to Monongahela in 1946, and signed up for the "52/20" club, a military program whereby he collected $20 per week for 52 weeks. This was a form of unemployment compensation to carry one over until he could find a job. Bob attended Waynesburg College on the GI Bill. He later served his country again during the Korean War.

An Interview with Roy Cox.

Roy Cox was born on February 18, 1922. He enlisted in

the Army in 1939 and was called to active duty in 1941. Roy began his

military career by joining the National Guard and was assigned to the

176th Artillery. Before being sent overseas, Roy went through boot camp

and participated in various training activities here in the United States.

He recalls that in early November, 1941, his company was traveling up the

east coast near Richmond, Virginia with military equipment. On that

journey, which was prior to December 7, 1941, his company was forced to

travel around the city of Richmond so as not to pose a problem for the

citizens,i.e., causing traffic snarls and allowing the civilians to

view unattractive army equipment in the streets. On December 8, 1941,

Roy's company traveled back down to Fort Mead, Georgia. For this trip,

Roy's company was guided right through the heart of the city of Richmond.

The crowds were cheering and waving to the soldiers. Roy's thoughts about

the two journeys can be summed up in the following quote: "What a

difference one month made. Before [the war] we were a nuisance, now we

were heroes."

At the end of 1941, while in England on maneuvers, a commanding officer noticed that Roy was not wearing his helmet. Roy often removed the helmet whenever he could because it bothered him. He had previously suffered a head injury at the age of 12, and the weight and tightness of the army helmet was quite troublesome. The commanding officer who spotted Roy without his helmet reported the incident to Roy's commanding officer. When he was called before the commander, Roy explained his situation. Needless to say, Roy's childhood injury caused the commander to immediately reassign him to non-infantry type responsibilities. After all, soldiers could not be removing their helmets while on the battlefield. After the incident, Roy was assigned to drive VIP staff cars in and around London for various military officers and dignitaries.

The officers that Roy drove included Elliott Roosevelt, son of President Roosevelt, Lt. General Lee, grandson of Civil War General Robert E. Lee, General Benjamin O, Davis, Sr., the first African American to achieve the rank of general and General Simpson, who was knighted by the King of England in 1945.

General Davis was in England to investigate a racially-motivated shooting that occurred. Roy explained that there was a great deal of animosity between the white and black soldiers. The soldiers lived in segregated barracks, but gathered together for entertainment in the small towns in and around London, such as Reading and Liverpool. On nights when all of the soldiers went into town, many fights would break out. An attempt to remedy this was made by assigning alternating nights for each of the groups, black and white, to go into the town. This, too, sparked arguments because the white soldiers were jealous that the African American men were taking all of the girls. On one occasion, the white men waited outside the entrance to the barracks and when the black men returned from town, shots were fired. General Davis came to London to investigate this incident as well as to try to enhance the morale and camaraderie among the enlisted. Roy indicated that he drove the General to many different barracks as he conducted his investigation.

The following story is one that Roy says is his most outstanding memory of his time as a driver. Upon the conclusion of the war, Roy was asked by his regular passenger, General Lee, to drive General William H. Simpson to Buckingham Palace to be knighted. General Simpson had successfully served as a commanding officer of American and British troops in Europe during the war. In recognition of his outstanding accomplishments, he was granted a knighthood by the King of England.

In the days preceding the big event, General Simpson and Roy mapped out their route to the palace from the General's hotel and made a "dry run" to assure that they had the timing down. Timing was of the utmost importance for security reasons at the palace. On the day of the event, Roy picked up the General at his hotel in the morning for another "dry run." This time they actually went into the palace and talked with the king's secretary who explained the procedure exactly, including where Roy was to park the car and which palace entrance the General was to use. Roy and the General synchronized their watches and proceeded back to the General's hotel. They each departed for lunch and agreed to meet again at 12:30 that afternoon, enough time for Roy to drive the General to receive his great honor. Roy went to the mess hall near Grovsenor Square and the American Embassy in London. He ate lunch and left the hall with plenty of time to spare, or so he thought. On his way back to pick up the General, Roy ran into a massive amount of traffic in Grovsenor Square because of a celebration, which included the presence of General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The crowds of people and cars prohibited Roy from passing through the square. As he waited amidst the crowds, he realized that he only had ten minutes to get to the General. Thinking quickly, Roy decided the only way to make it through the impenetrable crowds was to "disguise" his vehicle. The vehicles that Roy drove were equipped with various symbols including flags and decorations to display depending upon the rank of the dignitary that was in the car (for example, three stars for a three-star general, etc.). Roy unmasked the flag with the most stars--four--and placed it on the front of the car. Then, he turned on the lights and began sounding the horn as he proceeded. Because the black Packard limousine that Roy was driving was similar to those in Ike's procession, the policemen thought that he was part of Ike's group. The "Bobbies" cleared a path in the crowd and Roy was able to pass. As he proceeded, the crowds gathered around the car cheering "Ike!", thinking that he was in the back seat of the empty car. Roy, with little time to spare, hurried through the cheering crowd and knew, by looking at his watch, that he was just going to get to the hotel in time to pick up the General.When Roy arrived at the hotel, there was a taxi in front of his car, and he could see that General Simpson was in the back seat. The taxi pulled away and Roy decided to follow it. He hoped that at some point on the way to the palace, the General would look over his shoulder and see the decorated Packard and pull over to switch vehicles. He wanted the General to arrive at the palace in grand style.

Roy noticed that the cab was directed to the back gate when it arrived at the palace. After all, his car was the one that had been granted the security clearance. Roy proceeded through the main gates and was saluted by all of the guards. The commander of the guards ran over to the car to greet the General and escort him in to see the King. When he opened the door of the limousine, he was shocked to find that no one was in the back seat. Roy explained to the guard that the General was in the taxi that was going around to the back entrance of the palace. The guard then ran over to the taxi and directed it to the main entrance where the King's secretary was to greet the General. The cab then departed and Roy waited for the General to come out of the palace. The wait seemed like an eternity because Roy thought for sure that he was going to be in serious trouble because he had not been on time to pick up the General for this most prestigious event. After the ceremony, the General got back into the car and did not say a word until they got outside the palace gates. At that point, he said "Driver, pull over." Roy did as he was told, thinking that this was going to be his reprimand. To his dismay, the General leaned over the front seat, but not to reprimand him. With tears in his eyes, he showed Roy the medal he had been presented, and said "To think those people think that much of me Look at this beautiful medal they have given me."

Later that same evening, Roy chauffeured around General Simpson and other officers that were celebrating his knighthood. Roy heard General Simpson say to another General, "The King said to me, 'Leave it to an American to come to be knighted in a taxi. If it were a British officer, he would have come with a band playing.'"

There were many good memories that Roy had collected in his travels around the streets of London, but there were also some very scary times as well. On several occasions, Roy saw bombs being dropped and the debris and rubble that flew through the air as a result. On one such occasion, Roy remembers that, as he was driving along, a firebomb dropped directly in front of his car. Roy immediately fled from his Packard into the London subway station. He stayed there for a while, and then proceeded to inch his way up to see the damage. His heart was racing the entire time. Luckily, the bomb did not detonate and it was laying in the road in the exact location in which it had landed. Roy went back to his car, drove around the bomb and went on his way.

Roy showed me three large scrapbooks that contain various items from his 30-year military career. Among those materials he showed me was a piece of heavy paper, about 4 inches in length and an approximately an inch in diameter. One side of the paper was black and the other silver, similar to aluminum foil. Roy explained that this material was dropped in mass quantities from the sky by German planes in order to interfere with the allied radar. He said that this "paper" was scattered all over the London streets, so he picked up a piece of it, put it in his pocket, and there it was over 55 years later, well preserved in his scrapbook. After World War II, Roy returned home to McKeesport, Pennsylvania and attended his high school graduation ceremony. He showed me a newspaper article that contained a picture of the graduating class. More than half of the graduates were in uniform. In later years, Roy continued his military career during the Korean War and the conflict in Vietnam.

Conclusion.

The opportunity to interview these individuals has

given me great insight into what life was like during World War II.

Whether it was taking care of a young child here in the United States,

enlisting before you were old enough to join the military because you

wanted to serve your country, or driving dignitaries overseas, these folks

lived through one of the greatest conflicts of the 20th century. Though

their perspectives and experiences differ, they shared the same kind of

struggle that war inflicts upon all members of a nation.

The material memorabilia that each shared with me was meticulously kept and well taken care of. I was privileged to view some of their prized pieces of history, including ration books, newspaper articles, military medals, photographs and scrapbooks. Each talked of World War II as if it did not happen all that long ago. Their memories and recollections were vivid, and their stories numerous. I found it truly amazing that each individual was able to recall events that occurred 45 to 50 years ago with such clarity. It is apparent that a war as great as World War II had a profound effect on the lives of these folks. Their stories and sacrifices are a vital part in preserving the personal accounts of Pittsburghers for future generations. Without them, a part of American history would be lost.