Introduction.

Recording oral history was a new and daunting prospect

for me. Although I am not particularly shy, I am also not accustomed to

asking people personal questions. If a person volunteers information, I

am a ready listener, but I shrink from asking any question I would

consider prying. Therefore, it was with some trepidation that I began

this project. This uneasiness was likely responsible for my choice of

narrators. I asked my father and a woman who, before my mother's death,

had been her best friend and who I had known since childhood. These two

people, I thought, could be depended upon to help me, if only because they

knew how difficult I could be when a situation crossed me! Though it

should have been no surprise, the interviews went very well and they were

both very forthcoming about what they remembered of the period of World

War II. These are their stories.

Carmela English Takacs.

I first interviewed Carmela English Takacs. In my

lifetime I have known her as a homemaker and the mother of my friend,

Mariann. In the interview, however, I learned much about her life I would

have never known. She grew up on Cust Street in Glenwood. She grew up in

a large family. Besides her parents, she had four sisters and two brothers.

Both of her brothers attended Duquesne and became pharmacists.

She remembered that before the war the family kept up with the situation via radio. They were aware of what was happening. Carmela said about the beginning of the war, "It was sad. We were all upset hearing it. We didn't want to hear it." She said, also, "Well, I think people were strong during that time. Everybody sort of stuck together. I think everybody was trying to do the best they could." When the war began, her younger brother went to the service in the medical corps. Carmela had taken the job of a man who went to war. She was working as a time-keeper in a shop in East Liberty that repaired Cadillacs. "And I was mad because I only got half the wages at the time. The women only got half the wages of the men at that time...and I was doing the same work!" Her father died in 1942, while her youngest brother was overseas. It made her sad that he could not have been home at the time. Her mother had died in 1936, the year her sister Rose got married and moved east. In Philadelphia Rose's husband was involved in building warships. That left four sisters and an older brother at home during most of the war. "Yeah, we were one big happy family. We were happy. We were close. We're still close." Perhaps my favorite memory of those she recounted is only casually related to the WWII period, but it demonstrates what Carmela meant when she described her family as close. "The flowers...My brothers were good to us at that time and they used to always, if they were out of town or anything, they would always send us flowers. And my brother's nickname was N-U-N-S (his real name was John, but his nickname was Nuns), so he used to send his sisters flowers "from Nuns." And everybody thought we were nuns and sisters from the church. And they treated us royal and we got the best flowers from anyplace anybody ever got. They were beautiful. This went on for years, the same florist. They'd buy them, and our flowers would come, and they would be gorgeous. We were nuns and sisters...we were far from that! True story!"

I asked if she had been dating Frank Takacs, the man who later became her husband. Carmela explained, "I didn't start dating until I was, what, 25, 30? No, no, no...no, we dated, but we didn't do anything because the boys were coming and going. Well, the boys'd come home and visit and then go back...But (the four sisters) were together all during the war...but nobody went steady!"

Carmela recalls that they all worked and they are proud that their youngest sister, who was studying to be a teacher, attended the University of Pittsburgh. They valued education. Regarding war bonds, she laughed as she said, "Oh, yes, oh, yes...I bought them forever...until retirement. When queried about recycling, she commented, "I don't remember recycling a lot of things. 'Cause I think we used everything up!"

I inquired about what type of entertainment she remembered. She replied, "We all worked, and we all came home, and we entertained a lot...and everybody loafed at our house!" She said that her house at 76 Cust Street had a name and a motto: "Club 76-We doze, but we never close." Carmela explained, "(My father) let us do whatever we wanted at home...Well, we entertained ourselves because we had our own piano and record player...Everybody loafed at our house so we didn't have to go to clubs or anywhere else." She remembers her house was the first to get a TV.

I inquired about lack of silk stockings. Carmela laughed and said, "Well, we didn't wear them...we didn't wear any. In the winter you wore slacks and in the summer you didn't worry about not having nylons. We used to paint our legs with make-up for legs." Then she recounted this adventure. "I was in New York and I was on the subway, and a woman got up and left her purse. So I picked it up, went home, found her name and called her. I was at my sister's in New York (Rose was in New York for a short time), and she came to the house, got her purse...everything was intact. And she worked in a hosiery factory so she sent all of us girls nylons! So I was in with Flynn!" Carmela thought about it a minute and continued more softly. "She knew there was a bunch of girls...so she sent all of us nylons. And we treasured them...we treasured those nylons." But then she came back strong. "They were seconds, of course!"

When I asked about, Carmela responded, "I don't remember the coupons. I know my sister worked in a grocery store and she had to take coupons from people. But we were such a big family...There were enough of us. Everybody had a little job so we could take care of things and buy things...if we could get 'em. If we couldn't get 'em, we did without. And we were always handy, so we could make do. We could make something from nothing. We could make clothes. We do things like that. Fix our house, decorate. We did everything and we did it ourselves." Gas rationing didn't affect the family very much. Carmela said that her brother, who owned the only car, worked in the neighborhood pharmacy. Her father and the other girls took public transportation. When she traveled long distances, Carmela said she commonly took a train.

When questioned about what she knew of the horrors of the war, Carmela said softly, "Oh, that was horrible and, then, my brother sent us pictures and we would cry because...it makes me cry now...what the Germans did...I couldn't believe it when I saw the pictures. How they just threw them in a hole, tons of them. I still have the pictures. That was very, very sad." Her brother was stationed in France. He was in charge of the medications at military hospitals after the invasion of France. She recalls his letters being censored. "When my brother was in France and was trying to let us know where he was, he (wrote), 'This is a 'nice' place', and we knew he was in Nice, France...and they scratched it out. But we knew where he was."

One of the highlights of her brother's tour of duty in France, Carmela recounts, is his being the driver for Perry Como when he was on a tour entertaining the troops. "And then, while he was there, Perry Como was going to entertain the boys and (my brother) was going to escort him all over the place because we...the family knew him from way back when he was a young boy. And my brother was real happy to be able to say he knew (Perry Como), so they let (my brother) escort him all over the place and he was with him all the time. We thought that was real nice for my brother."

She recalls being shocked at the death of Roosevelt, but says the family was confident of Truman's ability. She said they read quite a bit. Of the atom bomb, Carmela recalls, "We didn't know to what extent it was going to cause what did happen...We thought it was going to be good because it might end the war, but we didn't know it was going to cause such devastation."

When asked how people responded to the news that the war was over, Carmela smiled and said, "Oh, that was a happy day! Everybody went to church that I knew of...we didn't know what else to do. We all went to church. We had a big parade and all ended up at church because you didn't know what else to do. We were just so elated! We prayed and we thanked God." Recalling the aftermath, she remembered that life gradually got back to normal. There were, however, reminders of the war. "Some of your friends came back and they weren't in very good shape. Some were OK. And some had lost their hearing. Somebody didn't have an arm. Somebody didn't have a leg. And some came back whole. In my family we were pretty lucky. They came back and in pretty good shape, too."

Frank Takacs, Carmela's husband after the war, was at Iwo Jima. For that reason, items about Iwo Jima draw the family's attention. Carmela asked me to note that an article by James Zumwalt on page 12 of Volume 123, Number 12 of The Stars and Stripes (05/22/00-06/04/00) shows the tenacity of a mother. One of the lasting images of WWII is the picture of six Marines raising the American flag on Suribachi, Iwo Jima. A woman, Belle Harlon, decided from a newspaper photograph that one of those Marines was her son, Harlon, who was killed a few days later. No one could convince her otherwise. One day after the war Ira Hayes, one of the six Marines, visited her. He said he wanted her to know that the Marine identified in the photo as Harry Hansen was really her son, Harlon Block. A congressional investigation revealed that Hayes was correct. Everyone asked how she could have been so sure. "Her answer: She had changed Harlon enough as a baby to be able to recognize his backside when she saw it." The article goes on to say: "The Iwo Jima photograph became the inspiration for the Marine Corps Memorial in Arlington, VA. And the fact that Harlon Block's name appears on the shrine as one of the six Marines who raised the flag testifies to the ineffable bond between a mother and a son." The importance to Carmela that another mother's story be recorded and remembered is what you need to remember about her.

John F. "Jack" McDonough.

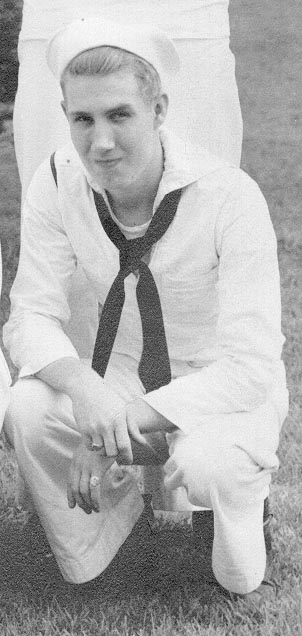

The second interview I conducted was with John F.

"Jack" McDonough, my father. Many of the stories he told I had heard

before, but usually in a random fashion as they came up in conversation.

This interview provided a clearer picture of the actual chronology of the

events. In contrast to Carmela's large family, my father's family was

composed of his parents, his brother and himself. He was 7 years older

than his brother Buddy. My father was born September 2, 1923. He is 76

at present. For much of his childhood he lived in the same house in

Hazelwood that he lives in today.

My father said, when asked about the Depression, that his family had not been affected as much as a lot of families. "My dad worked all the time, although he worked fewer hours in a week. But that was voluntary so that people wouldn't have to be laid off." He does, however, remember standing in line once with his friend, Bill, to get free food. My father said that Bill had no father and his mother taught piano to make money. My father's aunt and uncle lived next door and once, when Duquesne Light shut off their power, the family brought out a long extension cord and ran it from his parents' house to his uncle's so that they'd have light. He believes that the war got the economy back on its feet. "What Roosevelt did was give people hope. They put them to work on the WPA and such things as that. That took them out of the doldrums they were in before he was elected. But nothing he did solved the Depression," he said. My father did not doubt United States entry into WWII. "My idea was we were going to get involved sooner or later. It was not a question of 'if.' It was a question of when." When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, he was working as an usher at the Grand Theater with one co-worker, Mary Vitula. He said, "Ah...it was sort of stunning to hear it."

When we talked about those who didn't join the service, my father explained, "I don't really know of anybody who was deferred. I think Kelly Caterino would have been because of his eyes. Bud Quinlan didn't go. I don't know why, except possibly because his brother and his father were both killed. I don't think Charlie Darcy went. I don't know why. I know Bud...Bud Darcy created a ruckus when there was a possibility of Charlie's going, 'cause the other three of the four were already in the service. Everybody I knew was already there, was in the service. Jack Quinlan, Bill Marco and I enlisted the same day. We went downtown in Jack's car. But we didn't enlist in the same thing. Ed Smith left before us. And then Jack left. And then Bill left. I didn't leave till after Christmas, although I was sworn in on December 10th." He was 19.

"They had gone back to the full 12 weeks of boot camp. They had been shoving them out in 6 weeks, but they had gone back to 12 weeks. (Boot camp) was difficult, to say the least. Everybody was homesick. The food, we thought, was atrocious. We were getting all kinds of things we never ate at home. I tried to live on candy and ice cream and it didn't work. I spent a fair amount of time in sickbay. I was in sickbay when I was supposed to be going home on leave...at the end of boot camp. I had to talk my way out of sickbay. I was a day late. I went to the doctor's everyday when I was home and he treated me, but I wouldn't go to bed."

My father said that after that leave he attended radio school in Noroton Heights, CT, for 4 months. This was 1943. "They weren't in as big a hurry for people then," he said. When I inquired how he got his first assignment, he explained, "I got it in the lottery. They had so many ships and so many people. And they would ask who wants this kind of a ship or that kind of a ship." The officer counted hands, then asked the sailors to think of a number between 1 and the number of hands he counted. "And then he'd tell you, if you guessed the right number, then you got the ship. I got the USS Beatty, DD-640. It was...an unfortunate choice."

When asked why a destroyer, my father replied, "A destroyer is smaller, faster. It is the largest of the Navy's expendables. Certainly they'd rather lose a destroyer than an aircraft carrier. The armament (consisted of) depth charges for anti-submarine work, 4 multi-purpose 5" guns for anti-aircraft or land/sea firing, and twin 40mm. pom-pom and several 20mm. canon mostly for anti-aircraft and 4 torpedo tubes. Everything but the depth charges could be used against other ships or land targets. In the Atlantic they were used mostly to protect convoys or working with escort carriers (baby flat-tops) as hunter/killer teams searching for submarines In Okinawa, especially, they were part of the picket line that tried to shoot down the Kamikazes before they hit the big ships. During WWII 182 destroyers and destroyer escorts were sunk."

Once he was assigned to a destroyer, I inquired where they were sent. My father responded, "Wherever it went! They didn't tell us until we got there." He remembered vividly his first day aboard. "It was from New York to Casco Bay in Maine. I remember because I was seasick the first day. I recovered when we went through a canal which was like riding on the river. When I inquired what day to day life was like aboard a destroyer, my father replied, "Cockroaches...there were lots of cockroaches. My locker was full of them. You shook your clothes off before you put them on to get the roaches out. They walked down the table and nobody paid any attention to them." He said that, if they were close enough, sometimes they'd play the BBC radio over the public address system. Some ships had record players and ice cream makers, but not his. The first trip overseas must have been routine. "All I remember is that we anchored in the harbor at Bizerte (Tunisia) and that there was an air raid while we were there. 'Dirty Gertie from Bizerte'...there was a song or something like that.

"The second trip was more memorable. And ah...the second time we didn't get where we were going. We screened a convoy to England. We broke off and docked in Belfast. We spent six days there and stocked up on linens and laces for the folks at home. We left there and joined a convoy to the Mediterranean. We stopped at Gibraltar to refuel, then rejoined the convoy. We were the last ship in the starboard (right) screen. This was our position on November 6, 1943 when we were sunk." When I asked if he'd ever found out where they were going, he replied, "(I found out) years later. Read it in a book. Naples."

My father then described the sinking of the USS Beatty. "(It happened) in the Mediterranean. If it had happened in the North Atlantic, most of us wouldn't have survived." There were a couple of hundred people on the ship. Most of them made it. My father said, however, that his best friend on the ship, Joe Lees, was killed when they were sunk. "We were lucky. If you weren't, as I understood it, killed in the original explosion...killed or wounded there...then you were alright. One guy they picked up the next day with both legs broken. But he was still alive, floating in debris." The ship was sunk by an 'aerial torpedo' from a plane. He explained, "If it had been a submarine torpedo, it would have caused a whole lot more damage. We'd have gone down a lot faster. If the torpedo had hit a second sooner or later, it would have caused a whole lot more damage, because it would have hit the magazines. Well, the way it worked...we were all lined up, we were gonna get a ride. We only had two boats to begin with. And one of them took the wounded off and never came back. Well, there were other ships that were sunk, so they probably commandeered it elsewhere. And so we were all just...all standing up to get into the one boat...to be taken across to the USS Laub, really. It had got the propeller tangled up in the cargo net that they threw over the side for us to climb down. So the last I saw the boat they didn't even have oars for it. They were paddling it with a couple short paddles from the liferaft. At one time...the first trip...they had loaded a liferaft up and tied it to the boat and it was supposed to pull it, but the line separated and they just floated off. They picked them up the next day, too. But, by the time I left we were standing outside...we were listing to port, the left side, and we were standing outside the railing on the right, the starboard side. And a gunnery officer came by and said, 'Anybody who wants to swim come with me!' Well, I was a non-swimmer, but I didn't see much sense in staying there. I had a lifebelt. So, he tied a line and I slid down the line. I kicked my shoes off. And then I dog-paddled for a long, long, long, long way. There was an ensign. He didn't want to see me drown. He was swimming along side me. Yeah, he could swim. When I got to the ship, they had a cargo net over the side for us to climb up. But I was too tired to climb up. I just waited till (the ship) rolled down as far as it was going to roll and I grabbed on and they pulled me up, carried me over and sat me by the bulkhead. They weren't observing 'no smoking' and they gave me a cigarette and told me, when I felt like it, to go downstairs, take a shower and pick some clothes out. They had their own clothes, from that ship, from the Laube, they had just thrown on the tables in the messhall. (They) said try to find something that fits you.

"We hadn't had supper. We didn't have anything when we got there. We didn't have any breakfast the next morning. We didn't eat for almost 24 hours. (The Navy) put us on another destroyer, ran us down the coast and put us on a transport. Well, they put us in a compartment, which was nice. But when we got down to Oran...from Algiers to Oran...they moved us down into the hold and moved Army troops into the compartment. We took the Army troops up to Scotland, but we didn't get to see (it)...only Scotland in the distance. They put them in small boats and took them ashore in small boats. Then we went back to the States. We got 30 days survivor's leave then. I was home for Christmas and New Years."

My father said, however, that there was little to do at home on leave because his friends were all gone, all in the service. He does remember the conditions at home. "The mills were working full time. There were women working in the offices within the mill. There were women pumping gas and driving street cars. Every family who had males that were young enough had someone in the service. A lot of them had a blue star in the window. If the star was gold, the son or husband had been killed. Now that people had money, and unexpressed concern about the war and their people in the war, they needed a release. Nightclubs, dance halls and bars were among the ways they found it. There were lots of nightclubs. Jackie Heller (he had been a big band singer) had a yacht club down in the river that I went to. They left us in even though we weren't of age, but they wouldn't serve us anything to drink. They served us Coke. That was down on the Monongahela River, but it sunk. Also movies, especially patriotic (translate propaganda) movies. Every city had a U.S.O. Pittsburgh had one as you walked down from Penn Station toward Grant Street. Some people spent their spare time working there. Some religious organizations had centers, too, where people volunteered. In Spokane, Washington we patronized the Lutheran Service Center where you could get coffee, a sandwich or, if you signed up early enough, a bed. New York was the only place I encountered one, but other cities may have had them-taxi dance clubs. You bought a string of tickets and picked a girl to dance with. Every time a bell rang, you gave her another ticket. It cost 5 tickets (50 cents) a dance. We loved big band music and that's what the dance halls had. The radio was extremely important. For the news (Gabriel Heater's opening, 'There's good news tonight...'), for comedy (Fibber McGee and Molly, Jack Benny, Burns and Allen), and for music. After the 11 o'clock news, the stations picked up the big bands. In Pittsburgh they broadcast from Kennywood and William Penn's 'Chatter Box'."

About rationing, my father recalls, "Lots of things were rationed. Margarine (we called it oleo) replaced butter. In Pennsylvania it was illegal to dye it. It looked like lard when you bought it. A dye packet was included so you could mix it yourself. Meat and gas were also rationed. You couldn't get a new car nor new tires for the old one. Bald tires were common and tubes were patched and patched again. I didn't think of it at the time but, when I came home, I didn't bring ration points. So I was using my parents points."

After leave my father was stationed at the Naval Air Station, Quonset Point, Rhode Island. He explained, "I was a radio operator. That's the only place where I actually operated a circuit, where I sent as well as received. (The radio) aboard ship was all fox schedules...F, meaning broadcast. All you did was copy it and all they were was mostly five letter code groups that you couldn't break down. If they pertained to you, (the messages) would be broken down by the officers in the wardroom. They had the equipment to do that. We didn't." While he was at Quonset Point, he had opportunities to go off base. "Providence was where we went on liberty, although there were lots of small towns around there. We used to go to Appanog every once in a while. When we were going into Providence, there was one of the beer companies, one of the breweries, they had a room. We used to go there when we didn't have any money and sit there and drink their beer for nothing. And then go down and get free tickets to the dance hall. I went mostly to hear the music, because they had live bands. It wasn't recorded. They had lots of live bands."

From there my father was transferred to Shoemaker, California, which he didn't like at all. Near the end of the war, he was sent to Farragut, Idaho. During a physical, my father said, the Navy was looking at teeth, "and (the Navy) sent a whole trainload of us up to Farragut, Idaho, to get our teeth fixed. And by the time I got my teeth fixed, the war was over. But then, the war ended abruptly. None of us anticipated that kind of end to the war. I know what they were doing, what they were thinking. Getting ready for putting all these guys aboard ship for the invasion of Japan. And (the Navy) didn't want them to have any kind of ailment when they got them there. Especially teeth, which are so easy to take care of."

Regarding Roosevelt's death and the end of the war, my father stated, "I was...shocked., to begin with, and I was concerned about how the war was going to go from that point on, since (Roosevelt had been the leader for so long. I got to like Truman. I liked Harry. Even the use of the A-bomb. I think myself, that it definitely saved American lives. But I think it might have saved a lot of Japanese lives, too."

He said of Hitler, "Back then, I wished he would have lived so we could have hung him. He had an obsession...One thing you could be certain of, if he controlled the world, the Jewish people would be completely eliminated, as well as gypsies and anyone else who didn't like what he was doing." He believed at the end of the war that, if we were going to have to fight the Russians eventually, we should have fought them then, when we were all still over there.

I asked about what it was like the day the war was over. My father laughed. "The day the war was over I had the duty," he said. It was just another work day for him.

My father was discharged from the Navy on St. Patrick's Day, March 17, 1946. He returned, not to his home in Hazelwood, but to Carnegie, where he didn't know anyone. "But things had changed," he said. "I had changed. The country had changed. The world had changed." His friend, Jack Qunilan, had been killed. His friend Bud Darcy had been wounded. He went back to work at the mill, but after six months he decided to go to college. "The government was going to pay my way to college, so I quit to go college, to go to Duquesne." My father and mother, Gloria, married and had my sister and I. My father was in the reserves and Uncle Sam invited him back for the Korean War, during which he was stationed in Japan.

If asked about his life, my father would be sure to say that it was a very normal, average life. He has always been a rather easy going person, living calmly with my mother amid the chaos of kids, cats and dogs. He does not like parties and large crowds very much; he prefers a less social existence with family and friends. My father really did like big band music. We have a hundred or more records to attest to that. He has always like reading, particularly history, and travel, especially by train. He is still able to travel and does so often. My sister and I were fortunate to be raised by two intelligent, caring parents. They expected satisfactory school work and conduct. They allowed us to try any craft or musical instrument or art that we wished. They saw to it that we had free play time, which was as important as school to them. We had so many opportunities because of what they did and what they did without. I laugh when I recall that I didn't know that we were, relatively speaking, poor when I was growing up. I had to meet people who had money before I found that out. We just always had enough because our parents did without things for themselves.

I believe that the generation that fought World War II had a firm grasp on the importance of small, everyday aspects of life. They were people who grew up in the most important way in a very short period of time. They were entrusted at a young age with responsibilities that I would still shudder at assuming. Yet much of what I heard from my father, Jack, and Carmela was about the little things they remember, not the huge movements of the war, which both said they didn't follow very closely. They said they had a broad understanding of what was happening. Neither of them seemed to dwell on any problems of their own. They seemed happy with their choices and the outcome of their lives.

If there is anything I've learned from growing up amid the WWII generation, it is their willingness to assume tasks, both the courageous and the mundane, with the same basic self-effacing style. My father believes it is more important to persevere at mundane tasks, such as working for a living, because you get so many more opportunities to prove your worth. You may only get to be a hero once in a lifetime. You can work hard and support a family everyday of your life.

These are the ideas for living of the WWII generation: make do or do without, work hard, accept responsibility, protect others, stay close to your family, take advantage of opportunities for work, education and fun, travel, listen to music, dance. Enjoy the small pleasures of your everyday life. People have fought for your right to do so. They are not such bad ideas for living, are they?